Anyone who attended elementary, middle or high school in California will remember those routine earthquake safety drills where we had to crawl underneath our desks and wait for our teachers to tell us it’s time to come out.

Though they may have often seemed tedious and perhaps even unnecessary, the recent series of earthquakes in Ridgecrest – felt all the way down here in Westwood – serve as a reminder of the importance of earthquake preparedness.

For years, there’s been talk of the impending “Big One” – the catastrophic earthquake with the potential to seriously shake things up in California.

[RELATED: The Big One | Centennial]

Since the ground’s been quaking pretty frequently around here, it’s important to consider not only the validity of the term “Big One,” but also the seismic future of Los Angeles.

The recent commotion began on July 4 when a 6.4 magnitude earthquake hit near Ridgecrest, a city located 121 miles north-northeast of Los Angeles. Minor injuries and light damage were reported near the epicenter, but people felt the shaking throughout Southern California and as far as Las Vegas.

The very next day, in roughly the same region, a 7.1 magnitude earthquake quite literally shattered the desert floor. Moreover, ever since the tremor on July 4, Ridgecrest has experienced more than 80,000 aftershocks.

That’s the thing about earthquakes: They come in clusters.

David Jackson, a professor emeritus in UCLA’s Department of Earth, Planetary, and Space Sciences explained that earthquakes tend to occur in relatively fast succession.

“When an earthquake happens, there’s a greater chance that more earthquakes will happen near it in a reasonably short time and on the same kind of faults or with the same kind of behavior that the first earthquake exhibited,” he said.

This is one of the reasons why the term “Big One” doesn’t carry a whole lot of meaning in the world of plate tectonics.

“People talk about the ‘Big One‘ and that gives the impression that when a big enough (earthquake) occurs, that that’s the end of the story for a long time – earthquakes don’t work that way,” Jackson said.

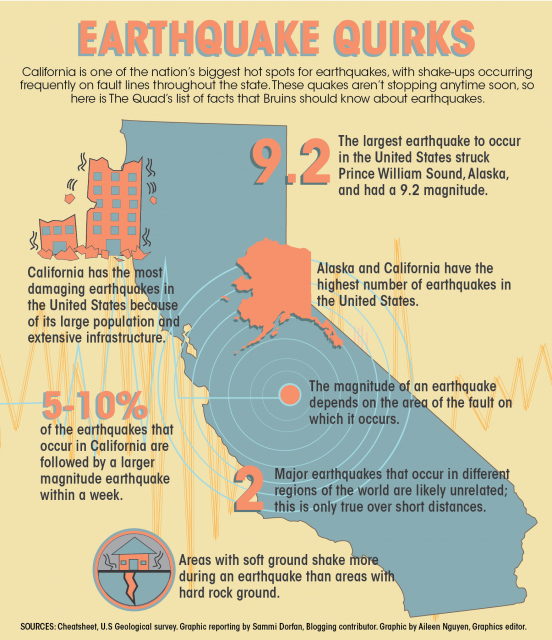

In fact, 5% to 10% of the earthquakes that occur in California are followed by another earthquake of a larger magnitude within a week. As a result, we won’t know if we’ve experienced the worst of it or if there’s still more to come.

While the term “Big One” was originally synonymous with the destruction of the 7.9 magnitude 1906 San Francisco earthquake, times have changed and similar magnitudes don’t necessarily yield similar amounts of damage.

For example, in 1994, Northridge was hit with the most destructive earthquake in U.S. history in terms of property damage. Its magnitude, however, was a mere 6.7 – smaller than California’s latest earthquake, which caused only marginal damage.

The brutality of an earthquake depends on its proximity to people and the resiliency of structures in the area. We can’t base the “bigness” of the “Big One” on the fallacy that larger magnitudes yield more damage.

Jackson said while there are many faults in the Los Angeles Basin, earthquakes that occur on undiscovered faults have the potential to be the most damaging since they could be located close to city centers without anyone knowing.

The infamous San Andreas Fault may garner more attention from Hollywood and the media than all of the unnamed ones combined, but that’s just one fault out of more than 500 in California.

The two most recent California quakes – as well as the 1994 Northridge one –occurred on fault lines that nobody knew about. Even though some fault lines are rather inconspicuous, seismologists are still able to identify areas with a high likelihood of seismic activity by looking at the patterns of previous earthquakes; this is how they formulate earthquake forecast maps.

According to Jackson, Los Angeles is on the edge of a red zone, which indicates a relatively high likelihood of seismic activity. Ridgecrest was similarly positioned on the forecast map in terms of likelihood.

It’s important to note that understanding the likelihood of an earthquake is different than predicting one, which simply cannot be done, according to the United States Geological Survey.

“There’s not any such thing as ‘overdue,’” Jackson said. “The dangerous part of this idea is … that when an earthquake happens there won’t be another one – that’s wrong and easy to see in looking at earthquakes around the world.”

Jackson recommends visiting a website called ShakeOut to find specific steps for preparing oneself for earthquake danger.

“When you hear the word ‘earthquake,’ do something simple to make your life safer,” Jackson said.

We may not know when, but the plates are moving under our very feet and Los Angeles could be the next big city to shake. In such a bustling metropolis with so many buildings and people who rely on them, earthquake preparedness is of utmost importance.