UCLA researchers identified a region of the brain necessary for learning and memory formation in rats, furthering researchers’ understanding of how memories are formed and stored.

In a study published in November, UCLA researchers in the lab of Gina Poe determined that changing the activity of an area of the brain known as the locus coeruleus during sleep can affect a rat’s ability to learn and form memories. The research may help explain the development or progression of some mental health conditions like Alzheimer’s disease and post-traumatic stress disorder that involve abnormal LC activity.

The LC is the region of the brain responsible for processing novel information, said Kevin Swift, a graduate student and lead author of the study. High LC activity is important for active learning, but, during sleep, low LC activity is necessary for integrating the day’s events into existing memories and forming new memories, he said.

“Normally, when you’re awake, (LC activity) is high and keeps (your memory) circuits strong,” Swift said. “(During sleep,) processing and updating these circuits requires less (LC activity).”

While researchers knew that the LC was generally less active during sleep, the relationship between lower LC activity and memory formation was not clear before, according to the study. However, they knew unusual LC activity has been linked to conditions like stress-induced insomnia, Alzheimer’s disease and PTSD, said Poe, professor of integrative biology and physiology and senior author of the study.

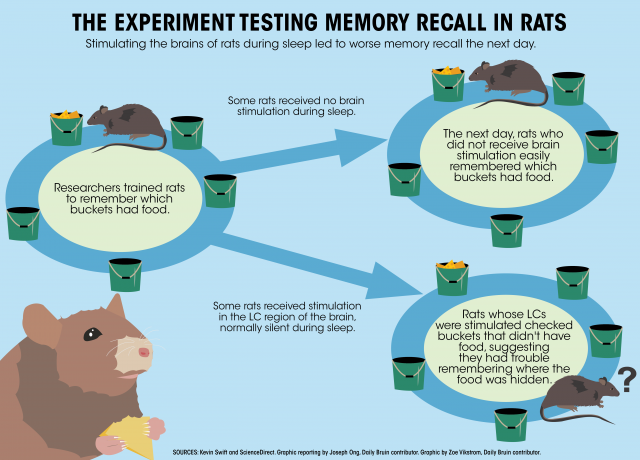

To study the effects of the LC during sleep, the researchers first taught rats a simple memory task using buckets placed along a loop. Some buckets had food, and others were empty. Rats were allowed to travel along the track until they learned which buckets had food and which did not.

Once the rats learned which buckets had food, the researchers altered the brain activity of some of the rats by weakly stimulating the LC of each rat during sleep, increasing LC activity when it normally would be less active.

The next day, the researchers presented the rats with the same track and hid the food in the same locations. While unstimulated rats remembered where the food was, LC-stimulated rats required more attempts to locate the food, suggesting they forgot their training from the previous day.

Moreover, when presented with a new track, LC-stimulated rats took longer than unstimulated rats to learn the position of food along the new track, suggesting they also had difficulty learning the new track.

These learning and memory defects were seen in LC-stimulated rats up to three days after they received the stimulation, according to the study.

When the researchers looked at the sleep patterns of these rats, they saw that LC-stimulated rats spent the same amount of time asleep as unstimulated rats. However, LC-stimulated rats had less of the sleep that is important for memory consolidation, said Michelle Frazer, a graduate student in the Poe lab. This may explain the impairments in learning and memory seen in LC-stimulated rats, she added.

Brooks Gross, another researcher in the Poe lab, said their research contributes to understanding and developing new treatments for conditions where the LC may not function correctly.

For example, Poe said that in some therapies for Alzheimer’s patients, the patient performs memory exercises to prevent or slow memory loss. However, the very act of accessing a memory will change it because it requires the patient to think about it, she said.

Similar to how LC-stimulated rats forgot their existing training, Poe said she is concerned that the combination of a weakened LC and memory exercises may lead to the distortion of existing memories in people with Alzheimer’s.

People with PTSD may have an overactive LC and, consequently, may store a traumatic memory too strongly, Gross said. This research identified a period of time after an event in which affecting brain activity during sleep may disrupt or alter traumatic memories, Swift said.

“(Our work demonstrates) you can interfere with this essential window (for memory formation),” he said.