UCLA researchers helped develop a smartphone-based microscope to detect parasites in bees.

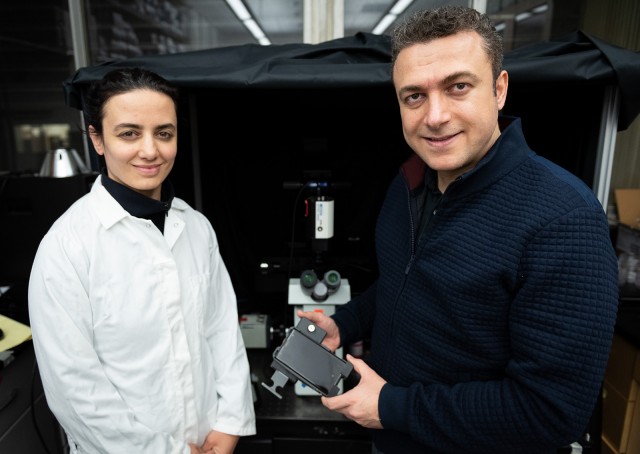

Aydogan Ozcan, the associate director of the California NanoSystems Institute at UCLA, developed a 3D-printed microscope to help beekeepers quickly determine if one of their bee colonies is infected with Nosema apis or Nosema ceranae, unicellular parasites that infect honeybees. Nosema disease has been called “the silent killer” because bees rarely show clear signs of infection.

Beekeepers will be able to attach a 3D-printed microscope to a smartphone device to view samples of a dead bee’s gut tissue. The bee gut samples are mixed with a fluorescent substance that allows the device to detect parasitic spores in the gut.

A mobile application on the smartphone then counts how many spores are detected and reports the findings to the user if the concentration is above a certain threshold.

Doruk Karınca, a fourth-year computer science and engineering student who helped develop the application, said it allows the user to take a photo of the prepared sample of bee guts with the smartphone. The photo is then sent to servers for the Ozcan Research Group at UCLA to evaluate with image analysis tools.

The microscope itself can be manufactured for less than $200 and the materials necessary to prepare the samples of bee guts can be obtained for less than a dollar.

“A traditional light microscope in a lab would be a few thousand dollars, more than 10,000,” Ozcan said.

Jonathan Snow, an assistant professor of biological sciences at Barnard College who collaborated with UCLA researchers, said Nosema parasites live inside the digestive tract of the honeybee and can be difficult to detect.

Snow added the parasites could contribute to the collapse of honeybee colonies. Bees are important in agriculture because they help pollinate crops.

Ozcan said the UCLA project was an extension of minor research he did at his lab and was an opportunity to help slow down the decline of honeybee populations, which he said is a major problem in American agriculture.

Ozcan said detecting parasites in bees is usually difficult because shipping samples to a lab can be inconvenient and slow. He added the microscope allows people to bypass this problem by doing tests in the field.

Snow said beekeepers could have hundreds of colonies and need a quick way to know which of their colonies are infected.

“Having a cheap and reliable test is important in order to quickly and efficiently decide on treatment,” Snow said.