These days, murder is a dish best served cold – with a side of social commentary.

If you go to theaters now, you will see this thought process in two movies. Riley Stearns’ “The Art of Self-Defense” and Ari Aster’s “Midsommar” both utilize violence to facilitate a larger societal message. While recent films focused on social commentary usually use violence to add a barrier to the oppressed group in the story, these movies feature such groups using understandable violence as a tool.

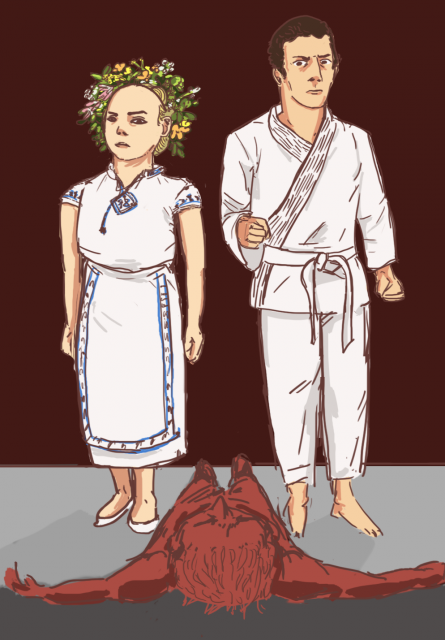

At first glance, the films are starkly different: “The Art of Self-Defense” is a black comedy featuring a feeble male who gets involved with an ultra-macho karate sensei, while “Midsommar” is a sunny horror flick about a couple’s failing relationship in Sweden. But for audiences with a discerning eye, their similarities rise to the surface. The leads in both films – Jesse Eisenberg and Florence Pugh, respectively – embark on a testing journey with the male antagonists – Alessandro Nivola and Jack Reynor, respectively. Both villains represent stereotypical masculine traits, as they are overtly aggressive and fearful of vulnerability.

[RELATED: Second Take: Boycotting is film industry’s right move to protest Georgia’s ‘heartbeat’ bill]

However, the most notable similarity between these two movies is that both Eisenberg and Pugh come into positions of power through murder, despite being initially perceived as weaker characters. Both murders move beyond the realm of senseless violence, as death is brought not only to male characters but to the masculine characteristics they stand for. The question then becomes, why choose violence as the vessel for social commentary when solving problems civilly is typically the solution?

While it is not uncommon for movies to include violence, the recent attention toward politically correct films with social commentary is somewhat unexpected given Hollywood’s penchant for action movies filled with empty violence. According to the American Academy of Family Physicians, 91% of movies and television shows contain violence, demonstrating that this visual medium has a long history of violence enmeshed with storytelling. Recent movies, however, have turned toward subjects with social relevance – but the levels of violence have not decreased.

“The Art of Self-Defense” and “Midsommar” both use their genres as vehicles to propel a deeper message about how people can and should fight against toxic masculinity. When Eisenberg kills the overbearing and cruel karate sensei, he is eradicating the notion that masculinity necessitates apathy. As for Pugh, her choosing her boyfriend Jack to die in the midsummer ritual is not murdering for the sake of murder, but rather cleansing herself from a source of toxic masculinity in her life. In this sense, both films have timely, gender role-based commentary.

[RELATED: Second Take: Black lead in ‘Little Mermaid’ remake brings welcome tide of representation]

The desire for social commentary in filmmaking is present in past films as well. The films that won the Academy Award for Best Picture a decade ago were “The Hurt Locker” and “The Departed,” but now, “Green Book,” “The Shape of Water” and “Moonlight” are taking home the Oscars. Most of the movies have violence in them to some degree, but the latter three use violence to show the hardships that minority groups go through. An example is how Chiron in “Moonlight” is beat up for being gay. The difference between the films a decade ago versus the films of today is that the former demonstrate violence for the sake of violence, while the latter feature less violence and are increasingly politically conscious.

But for “The Art of Self-Defense” and “Midsommar,” their violent endings weren’t senseless; they were instead symbolic of a more profound message. When Eisenberg and Pugh decided to kill Nivola and Reynor’s characters, respectively, audiences actively cheered for it. The revenge murders feel satisfying and freeing because they completed the arcs of the main characters as they moved from self-pity to the realization that toxic masculinity was the enemy all along. The violence coming from these characters – and not toward them – gave the moral of the story more agency than before.

So maybe audiences continue to crave violence, but it’s clear that people these days need justification – seeing violence for violence’s sake doesn’t have the same impact anymore. And while we might actively crave social commentary more than violence in our media, it will be impossible to ever fully dismiss our subconscious desire for violence.