This post was updated June 22 at 3:14 p.m.

Seemingly overnight, the once-obscure legal doctrine of qualified immunity became the center of attention of many news outlets and social media feeds. But, with all this present-day scrutiny considered, the question then becomes: what exactly is it?

In the wake of several recent and highly-publicized incidences of police brutality against Black Americans, there has been a resurgence of discussions regarding whether or not qualified immunity should be discontinued. Today, The Quad aims to dissect these calls for reform and bring more clarity to the complexities of this doctrine that has been used in many civil rights and police brutality cases.

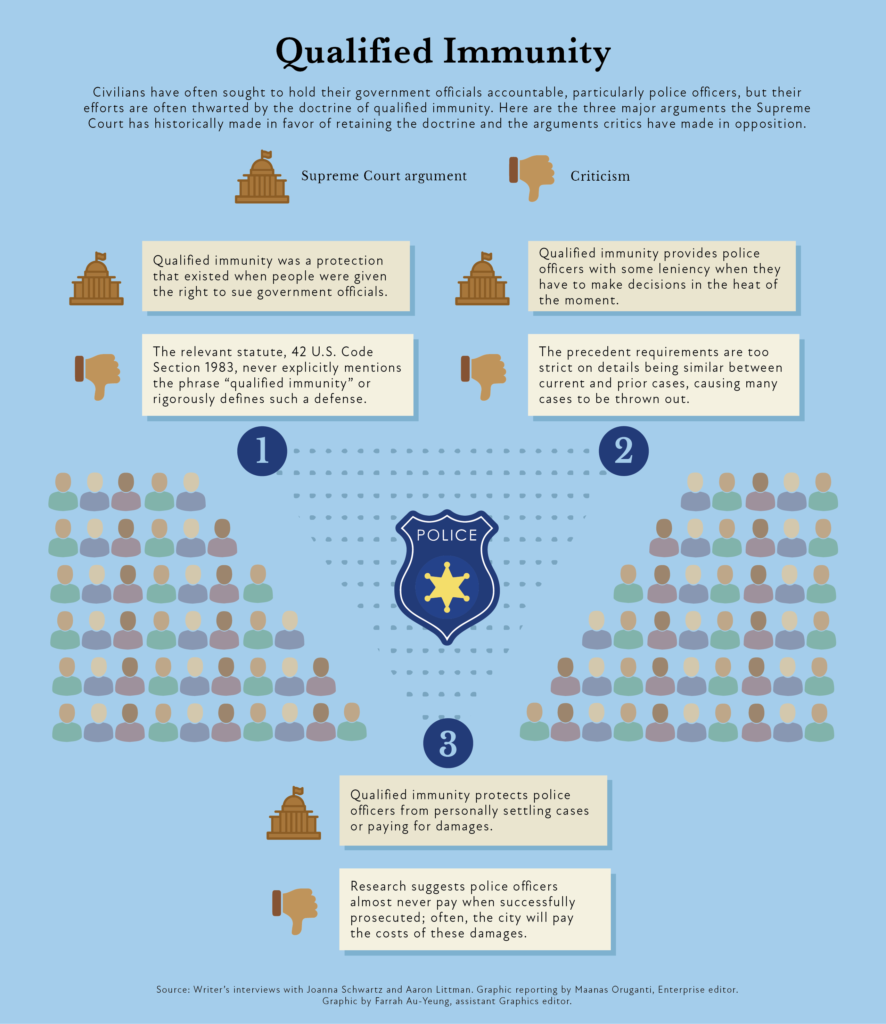

Qualified immunity is a judicial doctrine that affords protection for government officials, including police officers, in cases where they are alleged to have violated a civilian’s constitutional rights. Specifically, the protection allows for cases against officers to be dismissed if courts have not clearly established the allegedly violated right as guaranteed by the Constitution.

Joanna Schwartz, a UCLA law professor whose research was cited in a recent federal court decision on the subject, explained that there are very specific requirements, like the “clear establishment” of a constitutional right, that must be met to override qualified immunity protections.

According to Schwartz, to meet the “clearly established” requirement, there needs to be a prior case with almost identical facts to the case in question in which a court deemed the actions of an officer to be unconstitutional. Otherwise, Schwartz said, a case may be dismissed. This creates a loop: qualified immunity terminates a lawsuit because there is no similar case on the books, but there is no similar case on the books because the lawsuits are continually blocked.

Aaron Littman, a UCLA law professor and police accountability specialist, said if a civilian fled and was shot in the leg by a police officer, the civilian would need to find another case that clearly established the officer’s actions as unconstitutional.

“You might think that’s not so hard to do because there are lots of cases about people getting shot by police officers,” Littman said. “But what the courts have said is that you need to find a case that’s very precisely on point.”

Additionally, Littman explained that when qualified immunity was first established, the Supreme Court defined two steps to implement the doctrine. First, a court must check whether the alleged treatment by police violated a constitutional right. Second, the court must determine if that right was clearly established. However, the process has changed since its initial establishment and courts can now choose to rule only on whether the allegedly violated right is clearly established.

If courts were forced to determine whether an officer’s actions were unconstitutional, this could set precedents that could override qualified immunity in the future, Littman said. But because courts are no longer required to determine whether such allegations are violations of constitutional rights, Littman added, plaintiffs have a much more difficult time bringing cases successfully past the barrier of qualified immunity due to a lack of new precedents.

On top of this, Schwartz said that plaintiffs often face hurdles proving constitutional violations because of the Supreme Court’s tendency to defer to the expertise of cops in criminal matters and civil rights cases.

“The court has claimed that officers won’t have violated the Constitution if they acted reasonably,” Schwartz said. “Even if they acted in error, the Supreme Court has repeatedly cautioned that police officers, for example, are often making split-second decisions, and so shouldn’t be punished if they make mistakes.”

According to the Cato Institute, a public policy research organization, those in favor of retaining qualified immunity argue that officers should not have to think about abstract constitutional rights when making split-second decisions. Removing qualified immunity might make officers hesitate during critical moments.

But Littman said that it is the degree of this leniency that has become an issue.

“The problem is we’ve gone far, far beyond a little bit of leeway,” Littman said. “It’s one thing to say you can’t hold a police officer to the same standard as someone in retrospect because they’re acting in the heat of the moment. It’s another thing to say because there wasn’t a court case that clearly held that when a person is sitting up rather than lying down, you can’t sic a dog on them, the officer can’t be liable.”

Even if plaintiffs make it past the hurdles of clear establishment, Schwartz said juries and judges in many parts of the U.S. hold biases toward cops and against many of the plaintiffs, who tend to be people of color and/or have prior criminal records.

Among these barriers, both Schwartz and Littman said citizens and officials from all parts of the ideological spectrum have voiced their concerns about qualified immunity and have advocated for its dismantling. Nonetheless, the origin of the doctrine makes its potential removal more challenging than meets the eye.

Section 1983 of Title 42 of the United States Code, initially a part of the Civil Rights Act of 1871, allows citizens to bring accusations of civil rights violations at the hands of local and state officials to federal court. However, the Supreme Court has used the doctrine of qualified immunity in cases brought pursuant to Section 1983 to protect government officials, Littman said.

The Supreme Court has historically argued that qualified immunity helps balance police accountability against the interests of shielding officers from the burdens of constantly coming to court, Schwartz said. Proponents of qualified immunity additionally claim the removal of qualified immunity could have judges and juries examining split-second decisions and reaching verdicts that incur large costs for cities and public officials.

But, despite the Supreme Court’s use of the statute to justify claims of qualified immunity, Justice Clarence Thomas expressed concerns about using Section 1983 to justify the usage of qualified immunity in a dissenting opinion Monday.

Over the course of thousands of decisions, the Supreme Court established the doctrine of qualified immunity, which in and of itself is not a law Congress explicitly voted into effect. As a result, eliminating qualified immunity is more complicated than simply striking out a line or two from the U.S. Code, Littman said.

“A bill to repeal (the doctrine) would have to affirmatively say that this is not an immunity that applies or not a defense that exists,” Littman said.

Additionally, Schwartz said even if qualified immunity were to be repealed, the justice system would not radically change.

“I don’t think ending qualified immunity is some silver bullet and afterward civil rights litigations would look dramatically different,” Schwartz said. “There are still going to be many barriers.“

Lawmakers such as South Carolina Senator Tim Scott have argued there are other methods of holding officers accountable aside from revisiting or nullifying qualified immunity.

Even so, Schwartz stated that ending qualified immunity would shift the focus in civil rights cases away from precedents and instead toward the violations at hand, while also reducing the cost and time currently needed in these civil rights litigations.

“Briefing and arguing about qualified immunity takes time and expertise, so I think it would reduce some of the barriers to entry for lawyers who are interested in taking civil rights cases,” Schwartz said.

Schwartz believes the Supreme Court and lower courts currently send a message to officers that their violations of citizen’s constitutional rights will go unpunished. Similarly, these courts give citizens the impression that their rights can be violated with impunity, and ending qualified immunity would terminate these messages, Schwartz added.

All of this considered, the next thing to ask is: where does all of this stand today?

The Supreme Court decided June 16 that it would not review the qualified immunity doctrine despite numerous appeals to do so. Thus, it looks like changes – if they are going to come any time soon – will come from a different branch of government than the one responsible for the doctrine’s prominence.

As a result, though the future of qualified immunity remains uncertain, the movement towards confronting police misconduct is far from over. In the meantime, having a solid understanding of the doctrine and its origins will help Bruins to understand and to take a stand in the debates that will inevitably continue to unfold around it.