The COVID-19 pandemic and national demonstrations against the deaths of Black Americans have shed light on the brutal manifestations of systemic racism. Across humanity’s collective history, stories have elevated marginalized voices and breathed life into once broken structures. Through “In My Words,” community members and Daily Bruin staffers share their own experiences with racial identities and perspectives on the current state of race at UCLA and across the nation. If you have a story or an opinion you would like to share, complete this interest form.

Growing up in a former British colony had a lasting influence on the way I viewed race.

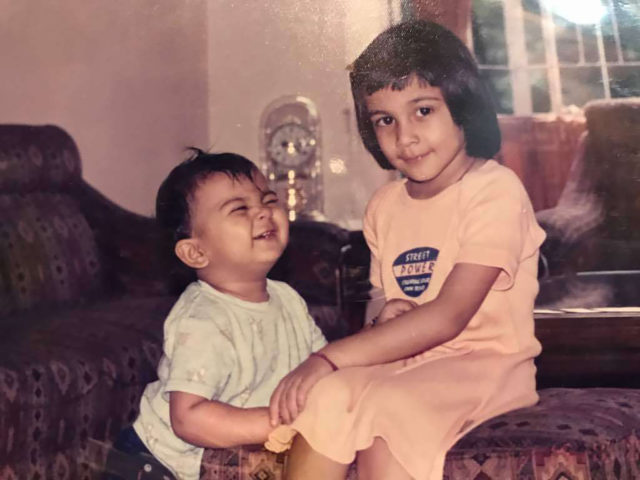

I was conditioned to believe that being light-skinned was somehow superior to being dark-skinned. I remember equating beauty with fairness as young as 5 years old, when I would get upset at my brother for saying that my sister was fairer than me. This was clearly a problem, but no one bothered to teach me that complexion doesn’t matter, that no skin tone is better than another.

It was my sisters who explained that it was wrong to judge anyone’s value based on the color of their skin. Becoming older and learning more about race in relation to others also gave me an entirely different outlook. I became aware that casual slurs were actually offensive after joining different social media platforms. In this global online community, I realized how nuanced racism can be – and how I needed to be conscious of my own problematic thoughts.

Colorism is rampant in India, with people believing that you have to be fair to be considered pretty and parents worrying that their daughter will have trouble finding a suitor because she is dark-skinned. This might have been born from generations of Indians being told their white masters were superior to them. The difference in skin color and the belief that the British were of a higher caliber caused Indians to fall further into the clutches of colorism.

When I decided to attend UCLA, I also decided to move away from everything that was familiar to me. I chose to move to a land of the “goras,” or white people. I was worried I would experience racism in America. When my sisters first moved to the U.S., people asked how they spoke English so well and whether cows roamed our roads. I expected similar questions would be directed at me, but was pleasantly surprised when I experienced no such incidents. The classmates and professors I’ve interacted with have been eager to learn about India and never asked racially insensitive questions.

But without noticing, I was playing into the theory that white people were superior to me.

I was showing a few white friends some Indian memes one evening when I realized that I was seeking their approval. This realization bothered me, and I decided to try to be more aware of how I behaved around white people. Slowly, I started noticing all the things I did to try to prove that I was equal to them. If I crossed a white person on the street, I’d change my walk. If I sat next to a white person in class, I’d be conscious of myself. I made an effort in all my interactions to show that India wasn’t a land of cows and snakes, but of cities and buildings.

It wasn’t my anger at anybody in particular that convinced me to push back against the idea that India is a land of savages. It was my desire to fit in. I was so desperate to be seen as stereotypically “white” because I believed that, at some level, being Indian was undesirable. I let the plague of colorism infect my brain and, in doing so, I had given myself an inferiority complex. When this realization dawned on me, I was aghast that I had internalized the very thing I despised. I’d allowed myself to erroneously believe that my brown skin decreased my worth as a human.

My third quarter at UCLA was different – I decided to firmly reject the stigma associated with dark skin. I no longer wanted to prove that India was a developed country or perpetuate racist ideologies. I was just focused on being a student and making friends, despite challenges brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic. I’m still working on accepting that I am in no way inferior and that I don’t need approval from a white person to be satisfied with myself.

No one should have to feel like they are less than another for something as basic as the color of their skin. Allowing myself to feel that way is an insult to those who are protesting against systemic racism.

Racial discrimination is an evil that has made its way to all parts of the world. And what many don’t realize is people of color can have racist notions as well. While being brown in an independent India never stripped anyone of civil rights, being dark-skinned subjected them to fairness creams and home remedies to lighten their skin. A dark-skinned girl’s fear of being deemed “unmarriable” in India is similar to my fear of facing racist remarks in America.

Racism is universal and must be treated as the plague it is. At a time when many are evaluating their positions in a global racial hierarchy, it is important that every person of color celebrates the skin they were born with.

Aastha Ginodia is a second-year economics student and is a Copy contributor for the Daily Bruin.