Cheyenne Cobb became a foster youth right before her senior year of high school. Placed in the care of her older sister following their mother’s death, the UCLA alumnus said she was not immediately aware the label “foster youth” was part of her identity. Initially, she believed the stereotype that foster youth were kids who moved from one foster home to another. However, upon admission to UCLA, Cobb said she learned of the numerous classifications that define foster youth, including the guardianship in which she was a part.

As an undergraduate student in 2019, Cobb started searching for ways to advance her growing interest in both the child welfare system and academic research. That’s when she stumbled upon the newly formed UCLA Pritzker Center for Strengthening Children and Families.

Established in 2018 with funds from the Anthony and Jeanne Pritzker Family Foundation, the Pritzker Center unites UCLA experts from various disciplines to research and reform the Los Angeles County Department of Children and Family Services – the largest child welfare system in the country. As of 2020, over 38,000 kids in Los Angeles County alone are using DCFS services, with Hispanic- and Black-identifying children comprising the bulk of cases.

The Pritzker Center also frequently collaborates with the UCLA Bruin Guardian Scholars, a program that advocates for and distributes resources to current and former foster youth at UCLA. Through the Pritzker Center’s partnership with Bruin Guardian Scholars, Cobb was hired as the center’s communications assistant. She now edits video content for its YouTube channel, such as webinars on juvenile justice, child abuse and the effects of COVID-19 on foster families. Cobb said the center frequently supports Bruin Guardian Scholars by hiring members of the program as its staff.

“It was an active effort on the center’s part to really try and find BGS students to hire,” Cobb said. “A lot of insights that we gave into our own experiences with the system and just being foster youth in general (were) super impactful.”

In particular, Cobb and her fellow Bruin Guardian Scholars members were able to speak with Lynn Johnson, the former assistant secretary of the United States Department of Health and Human Services’ Administration for Children and Families, in a meeting facilitated by the center. Cobb said she and her peers were able to share their experiences as foster youth, ensuring their voices were valued in conversations about how funding for foster youth programs has impacted their lives.

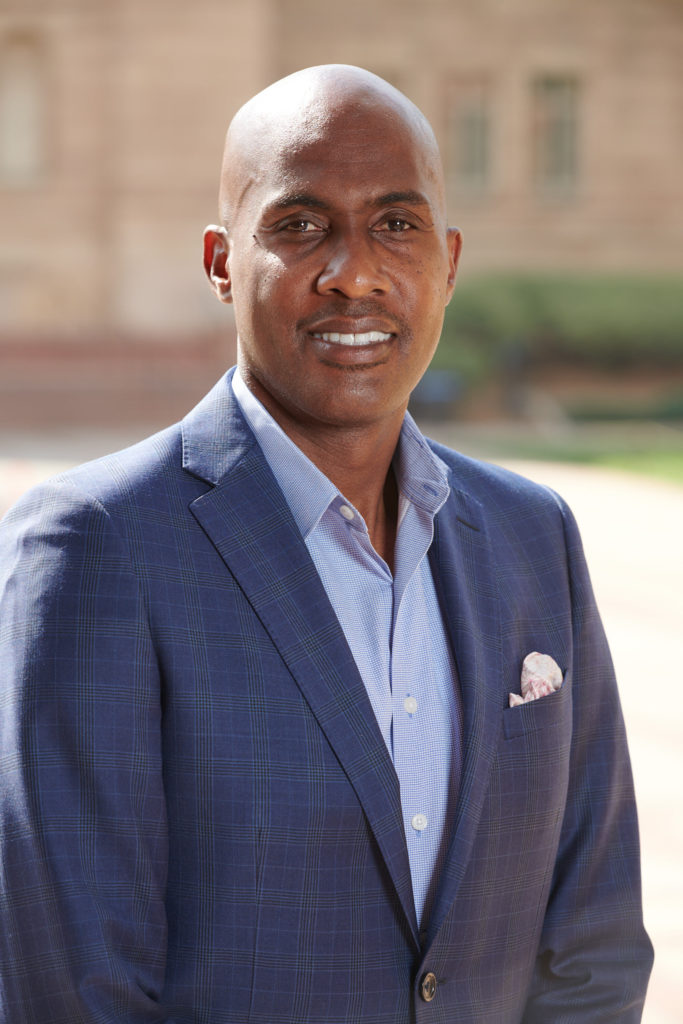

The center’s work aims to combine the knowledge of UCLA experts from a variety of fields, including law, social welfare, education and psychology to address the multifaceted challenges that foster youth face, according to Tyrone Howard, co-director of the Pritzker Center and a professor of education.

“What excites me about the Pritzker Center is that it’s multidisciplinary,” Howard said. “It brings together people from all aspects of campus who rarely talk to each other.”

The Pritzker Center demonstrates its multidisciplinary approach by funding a wide range of collaborative research projects, said the center’s administrative director Taylor Dudley.

“We have given out probably over $200,000 in seed grants to various faculty and staff across campus who want to work on innovative efforts toward improving the child welfare system,” Dudley said.

Recent seed grant initiatives include partnering with the UCLA School of Dentistry to improve foster children’s access to dental care and investigating the therapeutic benefits of dance for incarcerated young women in collaboration with The Swan Within, a nonprofit organization, Dudley added.

The Pritzker Center has also published two major reports this past year: one about child welfare and domestic violence and another about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on caregivers.

Specifically, the latter report studied the increased uncertainty foster families experienced during the pandemic.

The pandemic amplified the stress foster youth often face due to difficult transitions moving between homes, said Audra Langley, co-director of the Pritzker Center and a professor of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences. The loss and instability the world experienced during the pandemic parallels what foster kids experience on a day-to-day basis, Langley explained. The COVID-19 pandemic intensified the powerlessness foster children feel as they wait for adoptions or move to new homes, often losing important relationships with friends, pets, teachers or coaches, she added.

To study how resource families – caregivers for foster youth – coped with the “new normal” of the pandemic, researchers from the Pritzker Center, the UCLA Training, Intervention, Education, and Services for Families program and the Foster Together Network surveyed more than 600 LA County-based resource parents.

Published in September 2020, the report outlined some unexpected positive results that emerged from the pandemic. Langley and her co-researchers found that 68% of resource parents felt their families grew closer during lockdowns, despite fears of losing jobs or loved ones.

The center now plans to release a follow-up report in the winter to gauge how the events of the past year and a half have further impacted resource families, Langley said.

“We probably aren’t even aware of all the ways (the pandemic) impacted (foster youth),” Langley said. “What we were trying to ascertain in our study is how resource families are feeling about having children join their family during COVID.”

Though the pandemic’s full effect on the child welfare system is not yet apparent, the Pritzker Center has identified a key problem for foster families that escalated because of the COVID-19 pandemic: lack of academic support.

At the beginning of the pandemic, the Pritzker Center team discovered foster youth students’ need for tutoring through conversations with the Palmdale School District administrators, Howard said. Palmdale has the highest rate of foster youth in LA County, and many foster parents were struggling to assist their children with remote schoolwork.

The Pritzker Center started the UCLA Bruin Tutor Network in response to the rising need for academic support. Howard said UCLA students involved in the program tutor students in kindergarten through 12th grade in LA county, prioritizing foster youth.

“It was really powerful to see the way that UCLA students stepped up and volunteered,” Howard said. “We had over 300 families that were served, and these were all one-on-one tutors, and these UCLA students were phenomenal in terms of donating their time to connect with families, connect with children and to give them support.”

Brittney Hun, an undergraduate staff member at the Pritzker Center and a third-year human biology and society student, helped launch the Bruin Tutor Network. Alongside other staff members from the Pritzker Center, Hun helped virtually connect families with tutors for an hour of instruction each week.

“We want something stable for these students,” Hun said. “There’s so much changing in their lives, … but I think (stability) really does make a big difference.”

While the Bruin Tutor Network was able to recruit many tutors at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Hun said that recruitment has become harder as students work around their increasingly busy schedules. But for Bruins who want to connect with the Pritzker Center in a different way, there are many benefits to the center’s various trainings, workshops and speaker series, she added. In September, Angela Tucker, the founder of adoption blog The Adopted Life, will lead a three-part training series on transracial adoption and foster care, for example.

According to Dudley, UCLA students from all levels of experience with the child welfare system are welcome to both volunteer and work for the Pritzker Center.

“We don’t expect everyone to come work in foster care having been in foster care, … but one of the things that we look for is an eagerness to learn about the issues impacting children and families,” she said.

Dudley added that students’ lived experiences – such as coming from immigrant families or having incarcerated family members – can offer unique perspectives in their study of the child welfare system.

Nicole Yee, a UCLA alumnus, started working with the Pritzker Center in summer 2020. Yee was briefly involved with the foster care system when she was adopted from China and participated in Bruin Guardian Scholars throughout her time at UCLA.

Despite her time with Bruin Guardian Scholars, Yee said her knowledge of child welfare in the United States was limited. Hearing about the Pritzker Center’s UCLA Child Welfare Summer Academy piqued her interest in the subject.

The UCLA Child Welfare Summer Academy is an annual, three-week program that introduces the basics of the child welfare system to both graduate and undergraduate students at UCLA. According to Yee, highlights of the program include guest lectures and a movie screening.

Yee said her time at the summer academy opened her eyes to the scope of the child welfare system and helped guide her career aspirations.

“It was really impactful in the sense that it changed what I was going to do and it gave me some direction after graduation, when I really didn’t have any prior to that,” Yee said.

Following her time at the Child Welfare Summer Academy, Yee volunteered with the Bruin Tutor Network and contributed to the Pritzker Center’s report on child welfare and domestic violence. She now works as a legal administrative assistant at East Bay Family Defenders, a law firm which represents parents in family and dependency court.

As the Pritzker Center gears up for Bruins’ return to campus, the staff is also poised to take on a landmark collaboration with LA County’s DCFS.

The Pritzker Center will support a “blind removal” pilot program in LA County, in which identifying factors like race and zip code will be redacted when social workers decide whether to remove children from their homes and place them into foster care, Howard said. By withholding demographic information, researchers aim to prevent social workers’ unconscious biases from affecting their decision making, he explained.

The Pritzker Center will serve as an evaluator for the program and will analyze the work of a regional DCFS office.

In LA County, there are clear racial disparities in the population of the child welfare system compared to the county’s population at-large, Howard said. Black youth are three times as likely to end up in care than white youth, he explained.

“Why are Black children more likely to be taken away from their homes, why are Black children more likely to have allegations investigated, why are Black children less likely to be reunited with families or be connected with services?” Howard added. “Obviously, issues of racism loom large here.”

The pilot program will be modeled on a study conducted over a decade ago in Nassau County, New York. Howard is curious to see the impact of blind removals in a city like LA, which has so many children in foster care.

“We think it’s important because Los Angeles has the country’s largest child welfare system, so if there’s a place where we should be trying it, at least studying it, it should be Los Angeles County,” Howard said.

Cobb said she has valued how the Pritzker Center includes students and community members in its research and the effort it puts into making its resources accessible.

“(It is) providing a way for people who might not have been able to access this research … to now accessibly read it. They can see what’s being done,” Cobb said.