“’She Goes by They/Them’” is a biweekly series by Payton Kammerer, a nonbinary assistant Opinion editor. In these columns, they will be exploring a variety of queer issues, from those specific to campus life to those concerning broad public discourse. It is their goal to use this series as a platform to elevate the concerns of the LGBTQ+ community and also to provide an outlet through which people with shared experiences can find a sense of connection and solidarity. It is important to note that these articles are meant to serve as a starting point for conversation, not an end to it. Likewise, queer members of the Bruin community are welcome to submit op-eds or letters to the editor to be published as part of this series to create a product that does a better job of representing the many viewpoints of the LGBTQ+ community.

Imagine always being called the wrong name.

Not something close to your name, like a mispronunciation or a nickname, but something entirely unrelated to your actual name – a complete mischaracterization of who you are.

At a minimum, it’s annoying, a slightly uncomfortable social event that repeats itself, with no sign of ever really stopping. But sometimes, it makes you feel disrespected, question your own identity or even resent it.

That’s a small taste of what it can feel like to be nonbinary.

Recently, though, things have been different. A sudden change in the social landscape from primarily in person to largely online has resulted in an unintended phenomenon: visibility and a new control over it.

During the pandemic, Zoom has had a moment of shining glory: Many classes were or still are hosted live on the platform, and a lot of clubs and organizations have also adopted it.

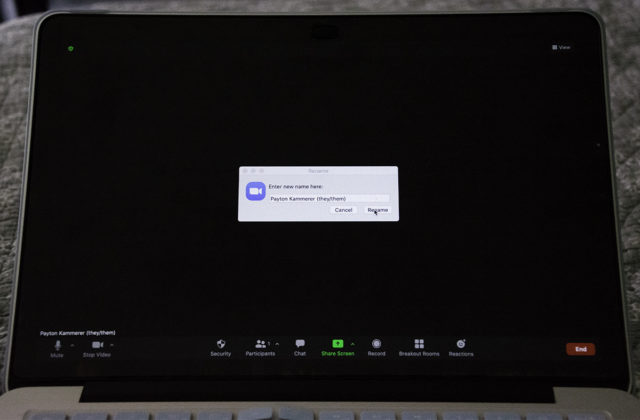

One feature provides gender-nonconforming people the opportunity to display, in full view of everyone on the call, the way they should be referred to.

If you’re out to that group of people, it can be a great way to help remind everyone, and if you aren’t, it’s a good way of letting them know.

The real boon, however, is that it’s entirely passive.

When typically you only have verbal options to let people know, you can now very casually tell them your pronouns without having to take up space in the conversation.

Krieger, a fourth-year environmental science student, said the freedom of changing their name on Zoom to include they/them pronouns relieved the burden of having to come out over and over again and sidestepped the question of whether to take the time to remind their peers of how they should be referred to.

Another benefit of this resource in a classroom environment is the way the increased visibility impacts others.

Nearly all nonbinary people have to live surrounded by people who aren’t. Being able to see another gender-nonconforming person publicly out in a classroom setting can be an immense relief.

In fact, being the same year and major as Krieger, I was in a few of the same classes as them this past year. Even though our interview was the first time we actually spoke, seeing them – and seeing our professors and peers respecting their gender identity – helped me get comfortable with the idea of coming out as nonbinary myself.

This is all not to mention the effect additional visibility has on binary audience members.

In nonvirtual spaces, when there aren’t good opportunities to passively share pronouns, people aren’t frequently exposed to gender-nonconforming identities, particularly in large group settings like lectures.

And when it comes to acceptance, awareness is a crucial baseline. According to UCLA’s own Williams Institute, a research group focused on LGBT issues, 76% of nonbinary adults in the United States are younger than 30. That pronounced age distribution has a lot of ramifications for the societal perception of nonbinary people, but the lack of social establishment for genderqueer identities in most spaces is particularly significant. Upper management, with its tendency to skew older, is almost always entirely composed of people in the binary.

But online, practices such as including pronouns in one’s identifying information have become commonplace, even for cisgender people. Those practices translated to Zoom readily, and suddenly a norm typically limited to social media became part of everyday professional life.

And that isn’t the end of where social media and gender freedom during the pandemic intersect. Anabela Nguyen, a genderfluid third-year theater student, said using his platform on TikTok during the period of online-only social interaction allowed him to explore his identity in a way he hadn’t been able to before.

“It’s kind of like a little practice run. It’s like, ‘OK, I get to try this on, I get to post this, and I get to present in a way that I want,’” Nguyen said. “And I’m like, ‘Wow, I can actually do this in real life too. … This doesn’t just have to be an outer part of me – it’s also this inner part of me too.’”

Unfortunately, the control that virtual socialization comes with can make resuming the in-person experience all the more frustrating. After a year and a half of being online, those of us whose gender identities don’t necessarily align with societal norms are once again subject to the unfiltered, uncaptioned gaze of our peers and all the opportunities for dysphoria that come along with it.

That isn’t to say that going back to real life feels like a burden for every person that prefers to live outside the binary. Like everyone else, we missed our friends, we missed connecting with new people and we missed living the lives we’d always envisioned for ourselves.

But for many of us, there is an additional bitter note in this transitional period, a downside to the return of normal to which almost no one else in our lives can actually relate.

If only we could pick which parts of “normal” to return to.