The UCLA Film & Television Archive is resurrecting the stories of incarcerated women.

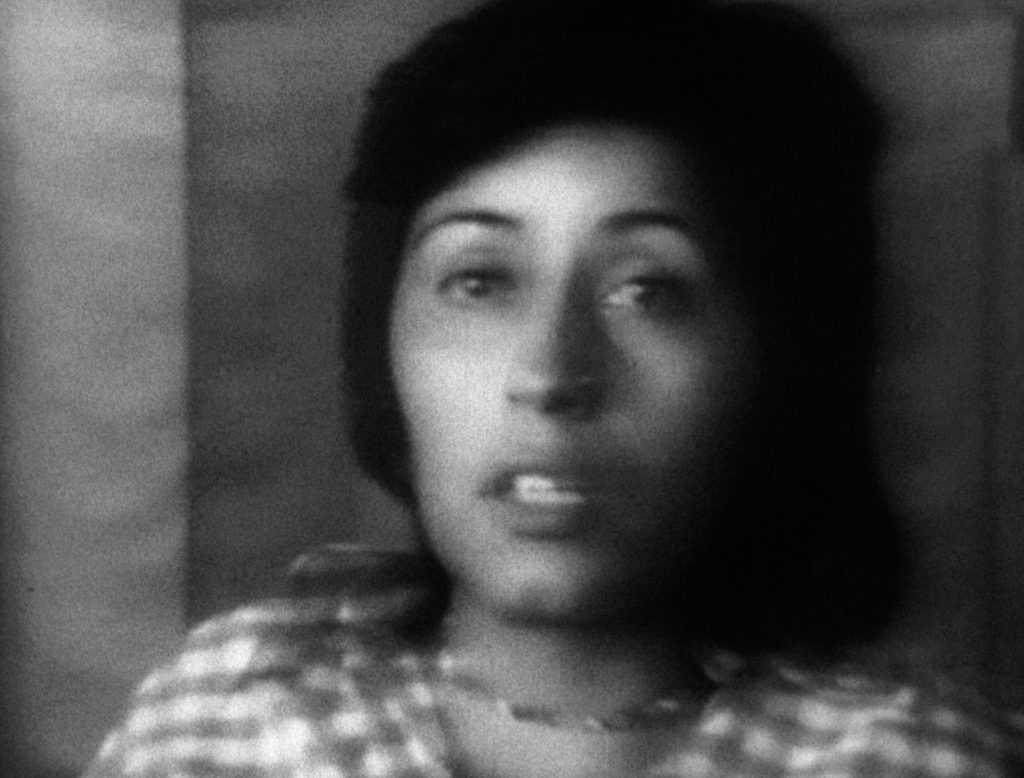

On Saturday, the Archive will screen a digitally restored version of “We’re Alive,” a 1974 documentary detailing the experiences of women at the California Institution for Women, a state prison for female inmates in Chino, California. The film, produced by alumni Michie Gleason, Christine Lesiak and Kathy Levitt, was made to cast light on the economic pressures and injustices within the legal system that led to the inmates’ imprisonment, Levitt said.

“The population of people in prison is mainly people who are poor or impoverished,” Levitt said. “We see a lot of people do many illegal things, but they’re never held responsible for it and they never do any prison time at all.”

[Related: UCLA archive to host screening of works by Black TV pioneer Robert L. Goodwin]

Prior to making “We’re Alive,” Levitt said she participated in various student demonstrations at UC Berkeley, such as protests against the Vietnam War. Gleason, who was also engaged in the anti-war movement, said she was involved in discourse surrounding racism and feminism. Although Lesiak was not as active in social justice, she said Gleason and Levitt invited her to join them to film the documentary since they were colleagues.

To gain inside access to the prison, Gleason said she, Levitt and Lesiak were told to organize a workshop that would prepare the women to enter the workforce after they were released. With this in mind, she said she and her co-producers collaborated with inmates, who helped make “We’re Alive.” The use of Portapaks, an early videotape recording system, placed a greater emphasis on the incarcerated women recounting their life at the prison, Gleason said.

“It’s essentially talking heads,” Gleason said. “There’s not a lot of aesthetic nuance to it. It was really more about getting the voices of women in prison out.”

Every weekend, Gleason said she, her co-producers and the inmates who volunteered would film and discuss an array of topics – most notably the influence of poverty and societal restrictions on women that led to their imprisonment. She said another recurring topic in their conversations was the prevalence of recidivism, the likelihood of a former inmate to commit the same crime. The institution was inadequately preparing women for life after prison, Gleason said, as they were not offered any kind of training beyond low-paying work traditionally done by women, such as hairdressing.

Because of the rising awareness of feminism in the ’70s, Gleason said she, her co-producers and the inmates found a shared ground in the lack of and need for women’s empowerment in American society. There was also a unique camaraderie and sisterhood one wouldn’t expect to find outside the prison, Lesiak said. While several women in the prison acknowledged this, she said they were still cognizant of the unfavorable living conditions in the prison.

“They (the women) are very self-aware,” Lesiak said. “They see themselves as in a place they’d rather not be, but they also don’t like the world that they’re going to have to come back into.”

Initially interested in the art house scene as a film student, Lesiak said “We’re Alive” changed her outlook on her career, as she started making more films surrounding social issues – specifically the injustices inflicted upon Native Americans in the United States. Moreover, Gleason said that, while she’s mainly made fictional films, she learned how to understand and empathize with different experiences because of “We’re Alive.”

Levitt said she and her co-producers did not credit themselves for the documentary until 2022, when she met two archivists who were coincidentally looking for the filmmakers of “We’re Alive” at a restoration festival. She and her co-producers did not include their involvement because they did not want to detract from the inmates’ personal narratives, Lesiak said.

“We didn’t really put ourselves out there because it was really a collaboration between us and them,” Lesiak said. “It was their ideas, their words, their perspective that we cared about. This wasn’t about us in any shape or form.”

[Related: Oscars 2022: Q&A: UCLA alumnus discusses class stratification in futuristic short film ‘Please Hold’]

Following the screening will be a Q&A session with all three producers and two former inmates at the prison, Romarilyn Ralston and Susan Bustamante. When Levitt and her co-producers first met with them on Zoom, she said they all realized how much prison conditions, including the low hourly wage, have remained the same since they filmed “We’re Alive.” Lesiak said she is glad Ralston and Bustamante will be speaking to their experiences directly during the event because of the lack of reform in the California prison system.

“They’re pretty much shadow people,” Lesiak said. “They are not seen or heard by society and that hasn’t changed. The fact that you go in there and you have no idea when you’re going to get out … that hasn’t changed.”

Comments are closed.