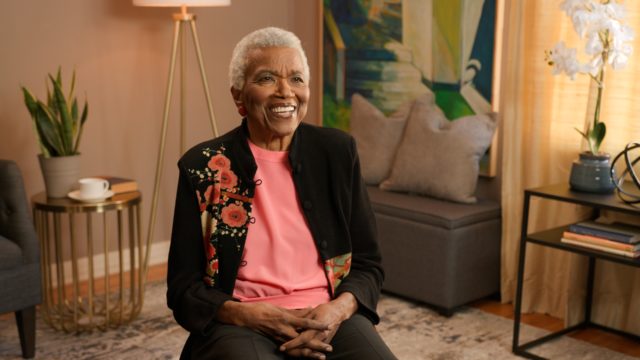

Jewel Thais-Williams, a UCLA alumnus, the founder of LGBTQ+ nightclub Jewel’s Catch One and an HIV/AIDS activist, died July 7. She was 86.

Thais-Williams opened Catch One on West Pico Boulevard in 1973 to serve as “a sacred space” for underserved communities of color, said Donald Kilhefner, who was a close friend of Thais-Williams for more than 40 years. The nightclub operated until 2015, according to the UCLA Library Film and Television Archive website.

Catch One was the subject of two documentaries in 1993 and 2016 – Jewel and the Catch and Jewel’s Catch One. The nightclub hosted many Hollywood artists and actors, Kilhefner added, including Madonna, Donna Summer and Lady Gaga.

“It became a beacon for Black, brown and other minorities in Los Angeles and around the country as the first club specifically designed for people of color,” Kilhefner said. “The club was open to anybody who wanted to come.”

Beyond acting as a safe space, Catch One was also a community center where substance abuse recovery groups – such as Alcoholics Anonymous and Adult Children of Alcoholics® & Dysfunctional Families – would hold meetings, Kilhefner said, with Thais-Williams herself having 40 years of sobriety at the time of her death.

Thais-Williams also transformed the building next to Catch One into the Village Health Foundation – a medical center providing alternative, complementary medicine – in the 1980s, after earning a master’s degree in acupuncture and herbalism from the Samra University of Oriental Medicine, he added.

“The space not only became a club but a community center and also became a medical center, which became very important during the AIDS crisis,” Kilhefner said. “During that crisis, those dark days of that pandemic, all kinds of fundraisers were being held at the club for individuals and for organizations that needed help.”

Catch One had a float in the annual LA Pride parade for many years and was one of the few consistent floats for years after it opened, Kilhefner said. Thais-Williams was then selected twice to be the parade’s Grand Marshal, Kilhefner added.

Mitchell Walker Jr., a LA resident who visited Catch One, said in a written statement that a friend of his would walk from Santa Monica, down to Catch One every Saturday night, dancing there until it closed and walking back. The trip was around 11 miles each way.

“People from out of town, Black people, brown people from out of town, sometimes before they went to their hotel room, they went to the Catch One just to be there,” Kilhefner said. “That’s what it was like – a Mecca, a sacred place.”

Thais-Williams served as a board member of AIDS Project LA – the premier AIDS advocacy organization in LA – for several years, Kilhefner said.

Harold Huttas, who served on APLA’s board with Thais-Williams for six years, said Thais-Williams participated in all of APLA’s efforts – including its volunteer and outreach initiatives – and attended all board meetings, where she often aided in the organization’s external communications for events.

She also co-founded the Minority AIDS Project, which focused on expanding access to AIDS treatment for Black and brown communities in Los Angeles, Kilhefner added. Today, the project offers in-home registered case management, specialty services, HIV testing and counseling, as well as health education, according to its website.

“Every time I think of her (Thais-Williams), I think of the word ‘inclusive,’” Huttas said. “The minority community was very ignored during that period by the government. The whole community was ignored by the government at that point. She’s an unsung hero, as far as I’m concerned. A heroine.”

Thais-Williams later co-founded Rue’s House with her spouse in 1989 to support women with children who were HIV positive and help them stay connected to their children, Kilhefner said.

She also donated funds to one of UCLA’s LGBTQ+ student-run organizations, he added.

The nightclub – despite its popularity and cultural influence – received backlash in the 1980s, Kilhefner said, with law enforcement threatening to close Catch One down. The building’s roof caught fire one night at around 3 a.m. – and although the fire department was able to extinguish the fire, Thais-Williams believed it was an act of arson, he added.

While Thais-Williams later sold Catch One in 2015, the new owners kept the nightclub’s sign in front of the building and created a mural in remembrance of the impact she made on the community, Kilhefner said. Thais-Williams then became a mentor and advisor for LGBTQ+ youth, he added, and connected people with resources they needed – whether it was lending them money or helping them to access a clinic.

Kilhefner said Thais-Williams believed she was brought into the world with “a suitcase full of gifts” from her ancestors – and that her lifelong goal was to give those gifts away to others who needed them. Thais-Williams – a supporter of the Civil Rights Movement – was open about her identity, and was committed to fighting back against injustice, he added.

“The Catch One touched a place of love in the hearts of many people in Los Angeles, particularly people of color and women, as a place where we could have fun, we could heal,” Kilhefner said. “And there was somebody there who was opening a door for us.”

Comments are closed.