This post was updated on Aug. 31 at 8:06 p.m.

Two years ago, the line for Panda Express at Ackerman Union seemed eternal.

Last year, it would rapidly grow at 11 a.m. and suddenly shrink at 3:59 p.m.

This coming year, there may be no line at Panda Express at all.

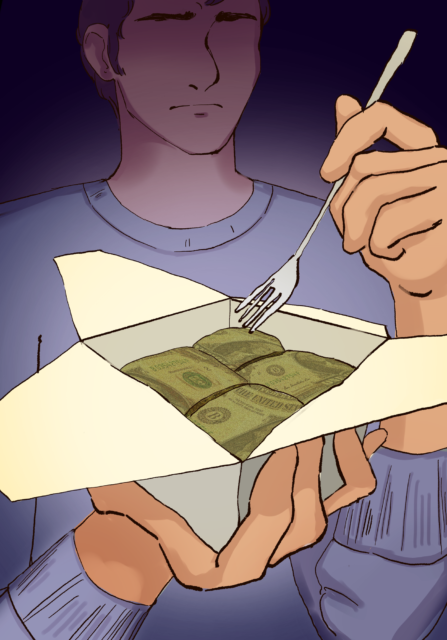

Non-ASUCLA-operated restaurants will no longer accept meal swipes starting this fall.

UCLA Housing plans to reduce costs through this campaign.

“When swipes are utilized outside of UCLA Dining venues, productivity levels decline, which dampens efficiency and increases costs on an overall per meal basis,” a spokesperson for UCLA Housing said in an emailed statement.

However, UCLA Housing owes us more of an explanation. After all, its decisions affect a community of over 14,000 undergraduate students living on the Hill.

After living on campus for two years, I feel rather bittersweet towards the occasional discomfort and high cost of my housing experience. Although UCLA Housing is a part of UCLA, which is nonprofit, it seems to me they are not reinvesting enough into the quality of housing and, furthermore, students’ undergraduate experiences.

When I lived in Sproul Hall and Hedrick Hall, I struggled to find personal space. Living in a 170-square-foot dorm with two roommates meant optimizing every inch I could, while ensuring that my personal habits and schedule minimized disturbances to my roommates. Upon moving out of the dorms, I feel like I have now seen and can endure every type of inconvenience.

Yet, this is not how the student housing experience should be. To begin with, the facilities often do not make life easier.

“A lot of the laundry machines are broken constantly, and I would pay for them before I find out that they’re broken, so that is a super frustrating experience to have,” said incoming second-year pre-psychology student Lucy Leer, who lived in Rieber Terrace last year.

On top of that, the limited availability of machines adds frustration to students’ experiences.

“Instead of doing all my laundry simultaneously, I have to wait for washers and dryers to open up, so it can take like six hours to do the whole process,” Leer said. “It is just super distracting when I’m trying to write an essay or something, and I’m just every 20 minutes getting up, trying to switch out a load or put something more in.”

Beyond the uncomfortable living conditions and unreliable facilities, housing costs can quickly spiral into a nightmare.

The classic residence hall triple, the cheapest room type under a nine-month contract, costs $9,254 – over $1,000 per month. On top of that, living on the Hill also requires a meal plan. The 19 Regular option, which gives its users 19 meals per week that cannot be rolled over until the end of the quarter, is $6,196, adding $688 to the monthly cost.

University apartments might skip the meal plan, but their rate is still steep. A two-bedroom apartment at Gayley Court, shared by five students, runs about $10,942, or around $1,200 monthly.

For comparison, a two-bedroom Westwood apartment for four people in August 2025 costs $3,797 total or $950 per person each month on average, according to rental platform Zumper, although furniture and utilities are not necessarily included in the contract.

In 2023, UCLA Housing made $19 million in net revenue, which contributed to accumulated earnings. These earnings are to fund future building renovations, development and acquisitions, said UCLA Housing in an emailed statement. However, this huge revenue is not sufficiently reinvested in students.

For example, UCLA Housing does not provide enough inclusivity to students with disabilities.

The Center for Accessible Education, which “provides expertise in determining and implementing appropriate and reasonable accommodations for academics and housing,” according to the CAE website, has a one-to-1,281 staff-to-student ratio, compared to the national average of one to 133.

We deserve a better housing model that prioritizes affordability and financial equality.

While this may seem impossible, an example already exists. The University Cooperative Housing Association (UCHA) is a nonprofit housing cooperative that provides around 400 students in Westwood with housing and 19 meals per week for an average of about $650 per month. Its maintenance relies on residents dedicating four hours each week to volunteer for chores.

“We’re not trying to take profits and turn them into part of our business plan,” said Darryl Sollerh, the executive director of UCHA. “They’re plowed always back into the buildings and just the necessities of running the place.”

Even with a limited budget, UCHA was able to redo all bathrooms and rooms with wood veneer flooring and paint the whole building this year, Sollerh said.

Why is UCHA’s housing model a lucky exception rather than the baseline? Our expectations are painfully low.

Students should not accept our housing reality as inevitable. If we can envision alternatives like UCHA, we can begin to raise awareness and advocate for a system that prioritizes affordability and accessibility.

“Remember, UCLA is a publicly funded university. And to me, that always means we should be able to serve as many of the public as humanly possible,” Sollerh said. “If you’re just focused on housing and supporting students with what they need, it’s doable as UCHA has proved for 88 years.”

Comments are closed.