This post was updated Oct. 9 at 10:45 p.m.

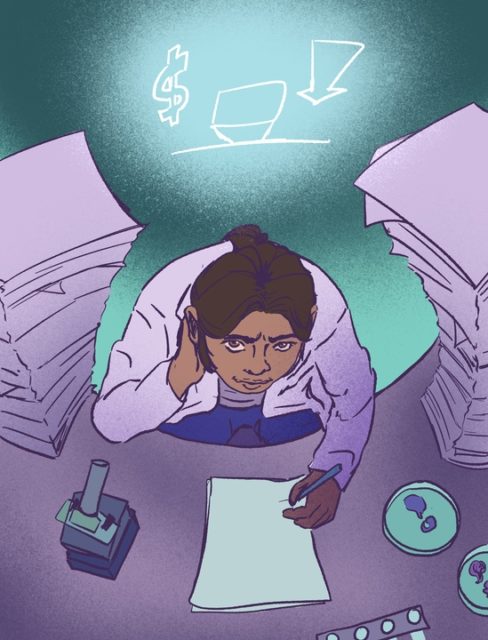

Graduate students and postdoctoral scholars said they are uncertain about the future of their pay and employment following the federal government’s cuts to UCLA’s research funding.

The National Institutes of Health, National Science Foundation and United States Department of Energy suspended about 800 of UCLA’s grants – amounting to $584 million – July 30 and July 31. The federal government alleged in letters explaining the suspensions that UCLA allowed antisemitism, illegal affirmative action practices and “men to participate in women’s sports.”

[Related: Federal funding cuts to UCLA]

UCLA’s NSF and NIH grants have since been temporarily reinstated following rulings by California federal district court judge Rita F. Lin on Aug. 12 and Sept. 22, respectively, in a case brought by UC researchers.

Some labs, however, are still under a hiring freeze despite the reinstatements. Some professors have also alleged that UCLA’s new hiring review process has impacted their ability to hire researchers.

[Related: UCLA professors express concern over new hiring review, limited student research]

Siobhan Braybrook, an associate professor of molecular, cell and developmental biology, said the situation remains uncertain. Lin’s preliminary injunction will only hold while the case makes its way through the courts.

Braybrook added that she believes the university should prioritize ensuring everybody is paid for their labor.

“Students are under contracts as GSRs (graduate student researchers) to be paid, and so, the question is ‘Where is that money going to come from if grants are suspended?’” she said. “That is what the UCLA administration is working on and needs to be covering.”

Toby Higbie, a professor of history and labor studies, said UCLA has a substantial amount of investments that it could put toward paying salaries.

Higbie, who is also the director of the UCLA Institute for Research on Labor and Employment, added that the federal funding cuts – and the fact that they have been politically motivated – are unprecedented.

“It’s important for students to understand this is an attack on the core funding structure of higher education in the United States as it has existed since the 1950s,” Higbie said. “What that potentially means is a catastrophic collapse of the entire system … (people) not just losing their jobs, but losing their careers.”

Celeste Medina-Seymoure, a postbaccalaureate student in biochemistry, said she works in the Catherine Clarke lab, which relies on one NSF grant.

When the NSF grants were first suspended, Medina-Seymoure’s principal investigator told them that they would be laid off from their position at the end of August, they said.

Although the NSF grants were reinstated, and Medina-Seymoure stayed in her position, she added that she still experiences constant stress over whether the funding will be suspended again.

“It’s definitely been a state of chronic stress,” said Ella, a doctoral student in life sciences who was granted partial anonymity for fear of retaliation against her lab from the federal government.

Ella, whose lab previously had its NIH funding suspended, added that UCLA has given its individual departments freedom to handle their respective funding situations as they see fit, since each department has different funding sources and structures.

While UCLA provided Ella’s department with financial support, she said graduate student researchers under different departments or contracts have not received pay – and have resorted to supporting themselves solely through working as teaching assistants.

Ella said that students not receiving pay have to work far more, as they would need to balance being a TA or holding another student job on top of their research.

Braybrook added that, while TA roles provide great teaching experience to graduate students, they also take away from the time students can spend on research.

Graduate students are often seen as having a dual identity as students and employees, Higbie added.

“My opinion is these people are full-time employees,” he said. “They should just be turned into full-time employees with a limited-term contract, and their job should be to conduct research, to teach and to do service.”

Aya Konishi, a doctoral student in sociology – who is a member of the bargaining committee for United Auto Workers Local 4811, which represents academic student employees, postdoctoral scholars and academic researchers – said the union is currently in contract negotiations with UCLA. Konishi added that one of the union’s main priorities is ensuring job security for graduate workers.

[Related: UAW Local 4811 pushes for immigrant protections, pay equity in UC negotiations – Daily Bruin]

A doctoral student in chemistry who was granted anonymity due to their position working for a senior university administrator said they do not have an issue with graduate students working additional hours of their own accord. They added that they believe it becomes wrong if PIs coerce students into working longer hours by threatening repercussions.

“I would not expect someone who was TA-ing for 20 hours a week to also be putting 40 hours of labor into the lab,” Braybrook said.

Ella added that some graduate students are also facing difficulties finding a TA role at all.

“It’s just kind of musical chairs,” Ella said. “There’s not really enough places for everybody who needs it.”

Medina-Seymoure said they are not able to become a TA as a postbaccalaureate student, adding that they have considered getting a part-time job outside of research to be more financially secure.

James Boocock, a postdoctoral scholar of human genetics in the David Geffen School of Medicine, said student researchers should not be forced to choose between their careers and financial security.

“We will end up enriching for a privileged group of people to be able to continue in the system, and a lot of people for whom we want academia to be for – working-class people – will have to quit,” Boocock said.

Braybrook said she believes UCLA’s limited funding could cause the university to follow trends of other higher education institutions – like the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Southern California – of hiring and training fewer postdoctoral scholars or admitting fewer graduate students in the future. Current undergraduates witnessing the funding cuts may also be deterred from pursuing further scientific training at all, she added.

“In a majority of the labs that I know, all the research is done by students,” Medina-Seymoure said. “If we do not have funding, things are not going to be learned. It’s plain and simple. We are the heart and soul of these labs.”

Comments are closed.