This post was updated Oct. 19 at 9:40 p.m.

The truth of “littleboy/littleman” is that growing up isn’t easy.

The world premiere of the grippingly honest play has arrived at the Geffen Playhouse’s Audrey Skirball Kenis Theater. Playing from Oct. 1 through Nov. 2, the show runs for 90 minutes with no intermission and features minimalistic props as well as a dynamic duo of protagonists – Bastian Monteyero (Alex Hernandez) and Fíto Palomino (Marlon Alexander Vargas). Brothers by blood, the two differed in last name and life goals but ultimately agreed to overlook their polarity. Directed by Nancy Medina and written with incredible deftness by playwright Rudi Goblen, “littleboy/littleman” struggled on comedic and meta levels but resonated deeply through its earnest portrayals.

“littleboy/littleman” excelled in its thematic storytelling above all else. Set in Sweetwater, Florida, Fíto and Bastian embodied two sides of the same coin. Fíto – a poet – was impulsively outlandish, whereas Bastian – a telemarketer – was cautiously authoritarian. Uniting poetry, brotherhood, live music and ocular rhythm, the production tells a tale of two brothers desperately trying to find success and safety within a world actively preying on their ruin.

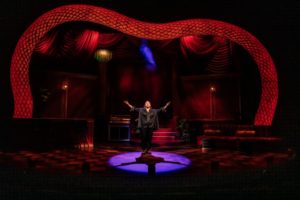

The readily impactful aspect of the show was its simplicity. The small stage, hugged on three sides by a limited audience of around 105 – and an additional elevated stage displaying the two-woman band – made the experience feel like one happened upon a glimpse into the protagonists’ life rather than watched a full-fledged production. Being seated merely feet away from the cast, viewers were sucked into the story with a sense of intimacy that would otherwise be lost in a larger theater. Thanks to the skilled lighting design by Scott Bolman, every scene felt distinctly unique in its mood and emphasis, and with each flash of the lights, the audience was flawlessly swept from one moment to the next.

The technical directness of “littleboy/littleman” extended to the actors as well – without the frivolous bells and whistles of a massively-staged production, Hernandez and Vargas commanded the crowd’s attention with heartfelt dialogue and perfectly timed execution. Telling the story of a modern-day American Dream from two clashing perspectives – Hernandez as the older brother and Vargas as the younger – Fíto fights over whether they should distance themselves from their childhood in Nicaragua or stay in touch with their scarring roots. With both – sometimes only one – of the two brothers on stage at a given time, the show benefited from its closeness in the ways their dialogue and intensity never dipped.

[Related: Theater review: ‘The Reservoir’ brings frequent laughs, which sometimes overshadow dramatic themes]

The show began with Fíto, surrounded by a ring of miniature traffic cones, as he delved into a lively street performance that lit up the room and piqued viewers’ curiosity through his three rules: “If you see anythin’ at all during this show you like, everybody please clap and make some noise … If you, see anythin’ at all durin’ this show that you do not like, guess what … you still clap and make some noise … when I [Fito] say alright, you say okay.” By starting the performance breaking the fourth wall, the audience was invited to experience the characters more deeply and, arguably, resonate with them more immensely by the end of the night. Fíto then shifted into a spoken-word monologue, which – illuminated by a spotlight and backed by snaps of the snare drum behind him – hit the crowd with line after line of cutting clarity and crucial honesty.

“You, sir, ma’am, will never understand what it takes to be a man [HAH!] comma [HAH!] when you’re a single woman raisin’ two of her opposites who have run a muck on the streets cause they know no better,” Fíto (Vargas) said during his monologue. “See, I was raised by two, mama and abuelita, with no macho in sight. So, yea, I cross my legs when I sit. Shit, I even sit when I pee. What? You don’t?”

Fíto’s spoken word is supported incredibly by the liveliness and sheer volume of the band, and bolstered by the theater’s crisp sound system and the production team’s excellently coherent synthesis of audiovisual techniques. At various times throughout the show, Fíto also entertained the audience with his command of the stage’s lights, which would click off or shift colors when he snapped his fingers. Such details and the direct incorporation of drummer Dee Simone and bassist Tonya Sweets do a remarkable job of adding to the intimacy of “littleboy/littleman” without ever taking the spotlight from its overall message.

[Related: Theater review: A meditation on Alzheimer’s, ‘Am I Roxie?’ finds its footing where memory fails]

Possibly the strongest scene of the show comes shortly after Fíto’s monologue, in which the brothers reenact a memory they share of the armed burglary and subsequent murder of their grandmother at home in Nicaragua. Choreographed to a tee, violently sharp with drum beats echoing as gunshots and lighting ominously cutting through fog machines, the actors’ movements mirrored each other with perfection as they acted out the moment. A result of the brilliant collaboration among stage director Medina, associate director Velani Dibba and movement director Christopher Scott, the show would have benefited immensely from more scenes such as this, yet its singularity made it significantly more memorable.

As both a comedy and a drama, the show’s former identity was much weaker than the latter. It seemed many jokes did not land as intended, such as when Fíto asked where audience members were from, then switched the locations like “Southern California” to “South Africa.” The faux-ending was similarly underdeveloped, in which Fíto appeared to return to his initial street performance to wrap up the show and ask the audience for tips. While it was a creative idea, its execution felt faulty and slightly predictable. Although it was meant to build to the dramatic finale, the transition’s shortcoming detracted from the important messaging of corrupt police persecution and the fragility of life.

Actors Hernandez and Vargas carried the show to triumph – worthy of a standing ovation – with their equally endearing personalities and profound moments of vulnerability. Both Hernandez, with his plethora of expert accents and zinging one-liners, and Vargas, with his captivating physical acting and ear-to-ear smile, brought their characters alive, making it hard to part with them in the end. While both took separate routes on the road to reconciliation, “littleboy/littleman” acknowledges “the better son” does not exist – whether it be through the offering of time or financial stability, Fíto and Bastian supported their family the best they could.

Magnetic, forceful and packed with relevancy, “littleboy/littleman” was a challenging watch – not in stagecraft but in content. Learning who the brothers were and how they got there revealed the crucial value of equal access and emphasized how challenging it can be to want what is best for someone while balancing their personal wants, as seen through Bastian’s tough love for Fíto. The show’s largest flaw lands on a meta level: Given that the story promotes underrepresented stories and the necessity of speaking out about the current system’s treatment of immigrant families, it is disappointingly counterintuitive that the stage’s intimate structure only allowed for a selectively small audience.

Immersive and current, “littleboy/littleman” works as a reminder that family is irreplaceable and dreams come at a cost.

Comments are closed.