This post was updated July 24 at 8:43 p.m.

A UCLA doctoral student was awarded a three-year fellowship from NASA in May to study the migratory movements of disease-carrying birds.

Ben Tonelli, a doctoral student in ecology and evolutionary biology, received this fellowship through the Future Investigators in NASA Earth and Space Science and Technology program after applying in February. According to NASA, the program accepted 62 out of 394 proposals in the earth sciences this year.

Tonelli said projects funded by FINESST must use NASA products and align with the agency’s strategic objectives, which are a list of research goals. Tonelli added that he will use satellite data and land cover maps to track migration as he explores NASA’s objective of understanding Earth as a system.

Morgan Tingley, Tonelli’s advisor and an associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, said most people think of NASA as an organization that explores outer space.

“A lot of what NASA does is to actually look back at Earth,” he said. “NASA has satellites that are constantly circling the planet and making observations in different ways.”

Tonelli added that he was encouraged to apply for the fellowship by both Tingley and Casey Youngflesh, a postdoctoral scholar in the Tingley Laboratory and previous recipient of this award.

Tonelli said his project combines his interests of how the environment affects bird migration and how diseases move from birds to humans. He added that his previous work in the Tingley laboratory has generally focused on how changes caused by climate and human activity affect the migratory patterns of birds.

“When we change the environment as humans, what does that mean for how diseases are moving around, and wildlife, and … our risk of contracting diseases and these spillover (transmission) events?” he said.

James Lloyd-Smith, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, said spillover transmission is the movement of a disease from an animal to a human. He added that this transmission can occur through a variety of modes of contact, including aerosols and food consumption.

Lloyd-Smith also said more research is required to understand why these risks may appear.

“For a given pathogen, and frankly, for a given animal reservoir that the pathogen could be spilling over from, … you need to understand, ‘Okay, how does it happen?'” he said. “In many cases, you can’t effectively mitigate (it) unless you know how the transmission is happening.”

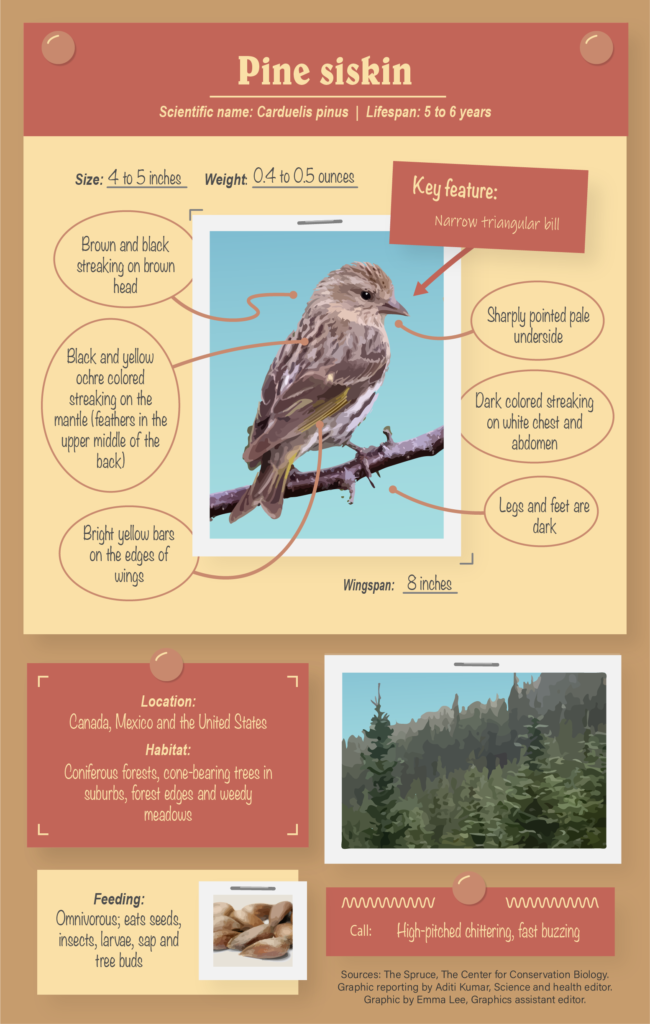

Tonelli said his project will focus on pine siskins, a type of songbird. Pine siskins are very social and often come to bird feeders where they can come into contact with humans, making them a good candidate to study disease transmission, specifically salmonella, he said. He added that he noticed the birds’ ability to transmit disease firsthand when they came to his own feeders.

“They’ll just … poop all over the feeder because they’re just sitting there eating and trying to survive themselves, but they’re just obviously spreading a lot of diseases that way,” he said.

Tonelli said pine siskins are also prone to what is known as irruptive migration, which is when birds significantly deviate from their usual migratory patterns. Though most people think of migration as a typical north-to-south pattern each year, certain birds like the pine siskin, whose movements are primarily driven by food availability, do not follow such strict patterns, he said.

Scarcity of conifer seeds in the Canadian forests, which are the siskins’ primary food source, forces them to abruptly move southward, Tonelli said, adding that this drastic shift is compounded by the increased food availability in urban areas from bird feeders.

Tonelli said his project with NASA is divided into two main parts: predicting irruptions and mapping the migratory movements of the pine siskin to understand disease risk.

The first part will involve using satellite data to observe environmental factors impacted by climate change such as temperature and precipitation, Tonelli said, adding that these factors impact food sources and therefore how often and how severe irruptions are.

This data collection is done through a process called passive remote sensing, Youngflesh added. Photons of energy from the sun reflected off the Earth’s surface are absorbed by these satellites, he said, functioning as a kind of digital camera sensor.

In the second part, Tonelli said he will use land cover maps, which provide information about whether regions are urban or rural, to determine what kinds of habitats the siskins are gravitating toward. This might reveal more about potential disease risks to humans and livestock from the birds, he added.

Tonelli said he hopes his research will contribute to protecting both the health of wildlife and human populations.

“Human health is linked more than we think to other populations, and the more that research is directed in that area, the better,” he said.

Comments are closed.